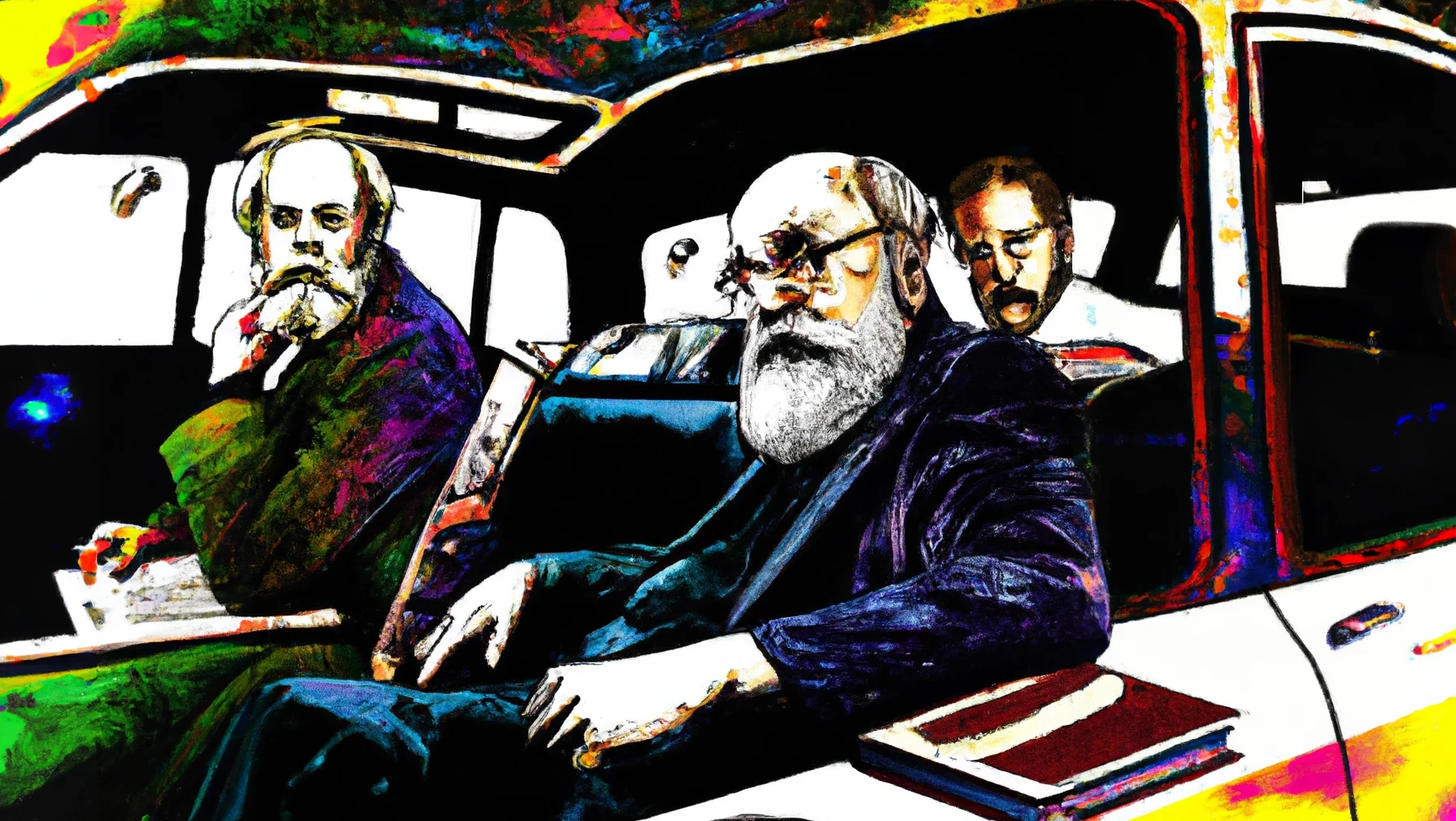

A historian, a theologian, and a philosopher are sitting in a car.

The historian says, “This car was made in 2016 in Indiana.”

The theologian says, “This car was made in 2016 in Indiana, but only because God as the ultimate creator of the universe allowed it to be made in 2016 in Indiana.”

The philosopher says, “When and where this car was made is an exceedingly difficult question. It is a 2016 model and was assembled in 2016, but the parts were almost all made prior to 2016. When did this car come into existence, considering each part was assembled in succession? Sometime before it left the factory and after the first two parts were attached to the frame, surely, but considering the engine block and frame predate 2016, was it perhaps 2015? An exact account of the origin of this car is very difficult. Moreover, a number of parts have been replaced and the car has been retitled. Is it still the same car? That is no simple matter. Moreover, the matter of which this car is composed is constantly moving on an atomic level, and so the car’s atomic constitution is constantly changing even if the changes in parts and changes in title did not lead to a new car originating after 2016 in place of the original 2016 car—if in fact the original car did originate in 2016. But suppose we resolve those issues. Still, we must not neglect the other issue of how the matter of which the car is composed traces back to the Big Bang–at least–which means that not only do pre-2016 parts of the car compose the car but those parts themselves are composed of matter billions of years old. So the ‘stuff of this car’ is unbelievably ancient even though this car was assembled in 2016. Therefore, by ‘made’ we obviously cannot mean ‘made’ in terms of ex nihilo creation. But I have been assuming that this car is an object with parts, and this is rather controversial. For suppose mereological nihilism is true and there are no objects with proper parts, and if so, then this car didn’t begin to exist at any point. But setting aside that significant issue, what picks out this particular car out from other cars of the same make and model and other cars that could have existed made of the same stuff of this car but do not in fact exist in the possible world that is actual? For even in this conversation I have used ‘this car’ to refer to a possible precursor to this car if in fact this car has not maintained its identity from the time of the assembling of a car—which may or may not be this car—in 2016 in Indiana. On top of all that, there is the conundrum of picking out what precisely ‘Indiana’ means and refers to. A place to begin would be Saul Kripke’s Naming and Necessity. Still, considering ‘Indiana’ only exists because human beings have agreed to designate such-and-such locale as ‘Indiana,’ in what sense does ‘Indiana’ exist? Would ‘Indiana’ exist in a world precisely like ours in every way except that ‘Indiana’ was spelled and pronounced ‘Yonkersylvania’? By ‘Indiana,’ are we referring to the geographic region irrespective of its legal name or to the legal entity? Moreover, does this car exist in a possible world—in the sense that if that possible world were actual this car would exist—in which the geographic region called Indiana in the actual world was not called Indiana, given non-identity reasoning and a compatible theory of identity such as assembly origin essentialism? But if it doesn’t, then is ‘Indiana’ being designated as ‘Indiana’ a necessary condition for this car to be this car, making all other conditions for this car to be this car—such as its physical origination and physical composition—insufficient for the identity of this car to be this car? But again, what is ‘Indiana,’ and is it objectively real? Surely, the region is not objectively ‘Indiana’ in the same sense two plus two objectively equals four. Surely a necessary condition for the identity of a car can’t be subjective or a mere fiction, can it? Or perhaps it not the truth of the proposition ‘Indiana exists’ but rather ‘people refer to such-and-such locale as Indiana’ upon which the identity of the car depends? But this introduces the issue of the nature of truth and whether, for example, the correspondence theory or the pragmatic theory is true. Is this car’s origin in 2016 in Indiana true because that corresponds with reality or because it is useful or beneficial or serves some other utility? So I’m afraid we are simply in deep waters in terms of what ‘this car’ and ‘Indiana’ refer to. Moreover, the idea that it was made ‘in 2016’ picking out a particular year sparks a great number of questions. For example, when we say ‘in 2016,’ we are referring to the past, but is the past as real as the present as on the B-Theory of Time or is the the past gone and done with as on the A-Theory of Time? For if the past is not real in the same way the present is real, then in what sense is it real? Is ‘2016’ merely real in the sense that ‘it happened,’ and if so, is it somehow more real than the future? How so? Moreover, is the past infinite in the sense that an infinite amount of time has passed in the past? For if so, then an infinite amount of time had passed in 2016. More time has passed since then, but even so, the time that has passed before the present day is still infinite. Is this coherent? Once one begins introducing questions of differing subjective dating systems, the relativity of time at various velocities, our perception of time, and again how names pick out specific referents—in this case, an alleged year—referring to ‘2016’ is no simple matter. Accordingly, that you say this car was made in 2016 in Indiana appears very doubtful. Moreover, I have ignored significant epistemic issues such as what knowledge is, how we know it, whether the Gettier Problem can be solved, and so on. As another example, if we are truly evolved and naturalism is true, then does Plantinga’s Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism have the disturbing implication that we are not justified about our beliefs about this car at all? I must deal with that as well, either by defeating his argument or establishing the existence of a cosmic designer, perhaps. But I am being too hasty here too by using terms like ‘we’ and ‘I’ and ‘think,’ given that it is quite debatable whether persons are conscious or that persons maintain personal identity through time or that persons exist at all in the sense we commonly think they do. We must not casually dismiss eliminative materialism, reductive materialism, epiphenomenalism, or similar theories—or the challenges raised by fission and fusion when it comes to personal identity. Might be worth reading Parfit just to begin that latter conversation. Of course, it might be the case that there is no material world at all such as on immaterial realism. In that case, there is no physical car, and so there is no physical car that came into existence, but that doesn’t necessarily mean there is no car. In what sense is there a car, then, and how can something immaterial be assembled in an immaterial place like Indiana? And then there’s the looming threat of epistemological solipsism and metaphysical solipsism. To keep things simple, let’s just consider the latter. Not only might this physical car not exist at all, you might not exist either. Maybe it’s just me, all alone, in this car. Oh, but there I’ve done it again, referring to ‘this car’ as if I know what I’m talking about.”